Identifying economic mental models and their flaws

The economic decisions that we make - and the mental models that govern those decisions - impact people and their well-being. Financial decisions persist undesirable outcomes when they are driven by assumptions (economic mental models) that need to be re-examined.

This learning segment gives change leaders context needed to challenge status quo economic thinking that often lurks behind resistance to beneficial change.

So crucial and so...fuzzy

Economics holds a unique position: Its so impactful and crucial and yet most leaders are so fuzzy about it.

Leaders need to develop a very clear understanding of how financial decisions impact the company bottom line, yes but also need an equally clear understanding of how their financial decisions - and accepted best practices - impact customers and their communities.

If you read the combined mission statements of the companies of the world, you'd get the strong impression that they are all focused on enabling healthier, wealthier communities. Yet year after year, we see the opposite.

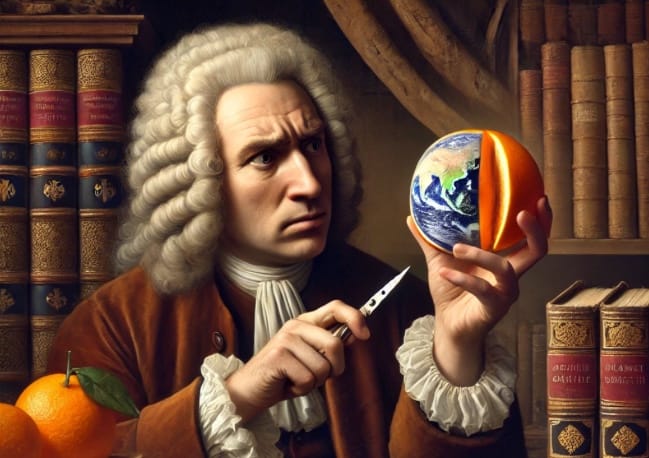

To enable healthier wealthier communities, we must rethink the things we've been taught about wealth and economics.

If you have ever faced individuals or companies who were resisting necessary change under the guise of financial necessity, this is the learning path for you. This will give you answers for those scenarios where someone says things like "that would be great, but we have to be practical" or "we have a business to run".

Understanding the Limits of Conventional Economics

Economics as we know it today is largely the product of well positioned and privileged people - a groupthink catechism of how privileged people in Western history have preferred to think the world works, and how they want everyone else to believe the world works.

In other words, economics is not how things work, but rather how those in control want you to think things work.

As Yanis Varoufakis notes in Economics is Irredeemably Sexist, the central theory of economics, "Homo Economicus", is a fiction invented and perpetuated by 19th century privileged white males steeped in power and a colonialist world view.

From this "rational actor" trope flows a stream of distortions and myths we carry around in our heads, reinforced by messaging from government and corporations. Collectively they perpetuate a sense of helplessness in the face of urgent and ultimately solvable issues facing our customers and communities.

Well intended individuals connected dots and developed ways of thinking that seemed to accurately describe the world as they understood it. Their work gave us a framework for thinking about economics and financial decisions...an economic mental model.

Today we have more context and our values have - thankfully - evolved. Our economic mental model needs to evolve as well.

If inclusion, social justice, equity, are goals we hold dear, we must recognize that our own economic thinking has been shaped by the assumptions and teachings of privileged individuals who in many cases did not share such goals. This point troubles conscientious leaders who want to their work and decisions to support beneficial outcomes.

How do we make sure that we're making decisions that lead to the outcomes we say we want, instead of just perpetuating the same old harms?

We all say we want better financial access, better equity and equality, better health and wealth for everyone. How do we make sure that we aren't working against these things?

- What specific points require us to relearn or rethink certain parts that we’ve always assumed what assumptions do we have to overturn?

- Is there someway of learning or adopting a new framework that helps me see things differently, and make better decisions without getting lost in a whole bunch of politically polarized, jargon and falling into extremes on either side?

- When we’re making decisions, what kind of considerations do we bring into the picture so we make decisions that allow our organization to thrive but also move towards the kinds of outcomes we say we want?

- How do we do our part to help drive financial innovation and better economic outcomes for a communities and customers?

- Is there something actionable, practical and constructive that can be done?

The good news is that - while these questions don't have neat little textbook answers - there is a path forward. A learning path that helps us deepen our understanding and raise the awareness of others.

It starts with learning how to recognize some of the more common flawed mental models that underpin our economic thinking today. Learning to recognize these flawed mental models is the first step toward making decisions and setting in motion operating patterns that enable the kinds of outcomes we all say we want.

Flawed mental models to be on the lookout for

Here is a short list of the conventional wisdom and assumptions that frequently guide economic decisions at both policy and organizational levels. If you are part of a team that makes decisions about pricing, access, processes, you likely have witnessed discussions where these ideas were in play.

The "Rational Actor" myth: Assumes individuals are rational actors solely motivated by self-interest, and will therefore always make choices that lead to the best outcomes on both an individual and a personal level. This pervasive idea - as noted above is rooted in narrow privileged 19th century viewpoints - and ignores basic realities like:

- The human capacity for impulsive choices and buyer's regret,

- The sheer difficulty of knowing the full implications of choices in a complex global economy.

- Proximity bias which causes us to focus on narrow perceived gains while ignoring social and environmental costs.

- Information asymmetries - for example where a seller knows things a buyer doesn't, and the buyer therefore enters into a contract or purchase that does not lead to a good outcome.

Trickle-Down Economics: This theory suggests that benefits for the wealthy will eventually reach everyone, but evidence shows it often widens inequality. It sounds reasonable, but simply giving the wealthy more buying/hiring power doesn't on its own enable the free circulation address the full set of needs in an economy. It does nothing to prevent misallocations of resources.

The Unseen Hand: This metaphor implies a self-regulating market that optimizes outcomes, ignoring power imbalances and market failures. This thinking often (correctly) notices the inefficiency and flaws of centralized regulation, but can over-correct by assuming that the complete absence of rules or guardrails. A more balanced view will recognize the value of intentionally setting expectations and incentives with specific outcomes in mind, and then measuring progress toward those outcomes. Public and private sectors can be partners in this effort, and can be aided by our increasingly powerful data and technology capabilities (the notion of a data driven set of incentives and goals may not have been actionable in previous eras due to the lack of data and compute capacity).

The Unseen Hand notion is often used to justify complete self interest free of any accountability or cooperation. There simply is no place in the universe where one can operate without accountability, cooperation or teamwork and expect that everything works out.

Zero-Sum Thinking: This mindset assumes that allowing any gains for one group will always come at the expense of another group. This is frequently used by more privileged players to argue against actions that benefit less privileged players. This can be corrected by focusing on collaboration for shared prosperity.

GDP as Progress: This metric measures economic growth but fails to capture well-being, sustainability, or inequality. These other measures should be considered. This essay shares more context on the limitations of GDP as a measure. The 20th century focused on the challenge of how to increase productivity. Here in the 21st century we face a new challenge: how to manage and protect ourselves from the hyper-productivity unleashed by AI, robotics and automation.

Actions to challenge these flawed mental models in our work and decisions

- Challenge your assumptions: Reflect on your own economic mental models and how they might influence your decisions.

- Make equity and justice the center of your team's decision making: Explicitly consider the impact of your choices on marginalized communities and future generations.

- Embrace new frameworks: Explore alternative economic models like doughnut economics or regenerative economics (links to learning resources in learning map below). This includes exploration of how you can use data to formulate your own measures for affordability, economic stresses, equality or other indicators of community health and wealth.

- Advocate for change: Speak up for policies that promote inclusive prosperity and environmental sustainability. Consider inviting guest speakers or conducting case studies to deepen understanding and help people see opportunities to apply their new understanding to the problems at hand.

- Experiment and collaborate: Partner with others to test innovative solutions and build a more equitable economy. Systemic change requires collective action. Encourage collaboration and advocacy efforts.

Key point: Recognize that each of us may have different roles to play, and may be able to have different kinds of impact.

For example, you may hold significant financial responsibilities in an organization that is risk averse or perhaps has thin margins. You may not have a lot of room to experiment or try radical new ideas - even though you may consider yourself an advocate for change.

But there are things you can do:

- you can introduce fresh angles when discussing decisions and strategies,

- highlight and humanize the people who are impacted by your decisions, and

- encourage higher awareness among your peers.

These modest steps can help generate very positive momentum and can support the more aggressive activities that others may be engaged in.

On the other hand, some change leaders work in completely different settings where there is a greater appetite for innovation and tolerance for risk. You may be working with emerging technologies, AI enhanced financial engineering, or Web3 /crypto. You have the opportunity to rethink and rearrange the financial building blocks that the economy runs on. Take the opportunities you are given - whether modest or radical in scope - to make things better.

Summarizing what you've learned

By understanding the limitations of conventional economics and prioritizing equity and inclusion, you can lead your team or organizations toward more just and sustainable outcomes. This journey requires a commitment to learning, critical examination, and the courage to challenge the status quo. Remember, this is a continuous learning journey, and your actions, however small, can contribute to positive change.

If you sum up our collective wishes and aspirations, it comes down to all of us wishing for and working toward a healthy wealthy world. Not just a healthy wealthy elite.

A healthy wealthy world: the S3T point of view

A healthy wealthy world is worthwhile outcome to work toward. A problem solving mindset that learns and works toward a healthy wealthy world will achieve more good than a pessimistic mindset that retreats into despair.

A healthy planet requires healthy ecosystems - including natural, social and financial. Healthy ecosystems require healthy communities. Healthy communities require healthy individuals. These are all sets of things that work together and impact each other. We must combine our individual skills and perspectives into sets of initiatives that effectively address challenges we face, and move us toward a healthy wealthy world. Not just a healthy wealthy few.

Nurturing the health and wealth of individuals, communities, ecosystems and the planet is a high calling that offers an opportunity for every person's diverse gifts and talents.

Continue developing your economic awareness:

This learning segment is a starting point. Encourage others to actively engage with the following resources and share their insights. These resources don't uniformly follow a single party line. Their problem definitions and recommendations may vary. But they all share a common willingness to challenge status quo thinking that enables economic distortions to persist.

- For healthcare leaders: Moral Hazard and Healthcare - Why Moral Hazard doesn't apply in healthcare - at least not the way we think it does.

- "Priced Out" by the late Uwe Reinhardt, former professor at Princeton, advocate for healthcare affordability, and conscience-driven thought leader in healthcare policy. Summary of his life and thinking here. | Review of last book Priced Out here | Used copy on Alibris.

- "Capital in the Twenty-First Century" by Thomas Piketty: Deepen your knowledge of wealth inequality and its dynamics. Used copy on Thriftbooks. | Short HBR review here.

- "Doughnut Economics" by Kate Raworth: Guide for 21st century economists who see the need for an alternative economic model focused on social and ecological well-being. Summary here. | Used copy on Thriftbooks.

- "Designing Regenerative Cultures" by Daniel Christian Wahl: Learn about building regenerative economic systems. Used copy on Abebooks | Introduction to the book published by the author on Medium. | The economics of sustainability.

- World Inequality Lab: Access data and research on global wealth inequality.

Click here to continue to the next learning segment: Gaining buy-in for data modernization:

Some of the world's most transformative AI use cases are waiting for data that is currently locked up inside legacy platforms and policies. But data modernizations are fraught with complexity, costs, and perhaps worst of all politics. How to inspire and guide an organization to leave behind its status quo and embark on a data modernization journey.